Under the dome

- Paul Dobraszczyk

- May 27, 2016

- 4 min read

Buckminster Fuller’s 1960 project for a 3km diameter dome to protect Manhattan from air pollution and to control its climate.

‘The round cry of round being makes the sky round like a cupola’ Gaston Bachelard, The Poetics of Space, p. 238

Domes are as old as architecture itself; some of the very earliest known structures – for example, 5,000 yr-old burial sites in Scotland, Ireland, Denmark and Malta – are shallow domed mounds hewn from inside the earth. Strongly associated in religious buildings of all kinds with an image of the life hereafter, domes have always encapsulated our desire to feel comforted in the face of the enormity of the world beyond, whether that world is imagined as below or above the surface of the earth.

Megalithic burial site at Newgrange, Ireland

The central dome of the church of Haghia Sophia, Istanbul, completed in 537 and converted into a mosque in 1453.

Etienne-Louis Boullé’s proposal for a gigantic cenotaph for Isaac Newton, 1784

In the modern scientific era, the overtly religious symbolism of domes might have waned; yet that ancient craving for comfort in the face of unknown forces has persisted. Even as Etienne-Louis Boullée’s series of imaginary tombs and cenotaphs to great Enlightenment figures such as Isaac Newton used monumental domes to signify the triumph of reason over fear, the iron-and-glass domes of countless 19th-century exhibition halls both frightened and reassured visitors as to the unprecedented powers unleashed by industrial capitalism. The sense of disquiet in the face of these powers would, of course, intensify in the 20th century, the second world war concluding its orgy of violence with domes of a very different sort. Here, the miraculously preserved remains of Hiroshima’s Product Exhibition Hall (now the Genbaku Dōmu or Peace Memorial) have come to symbolise the unimaginable power of another domed structure, namely, the blast cloud from Little Boy which exploded in Hiroshima on 6 August 1945.

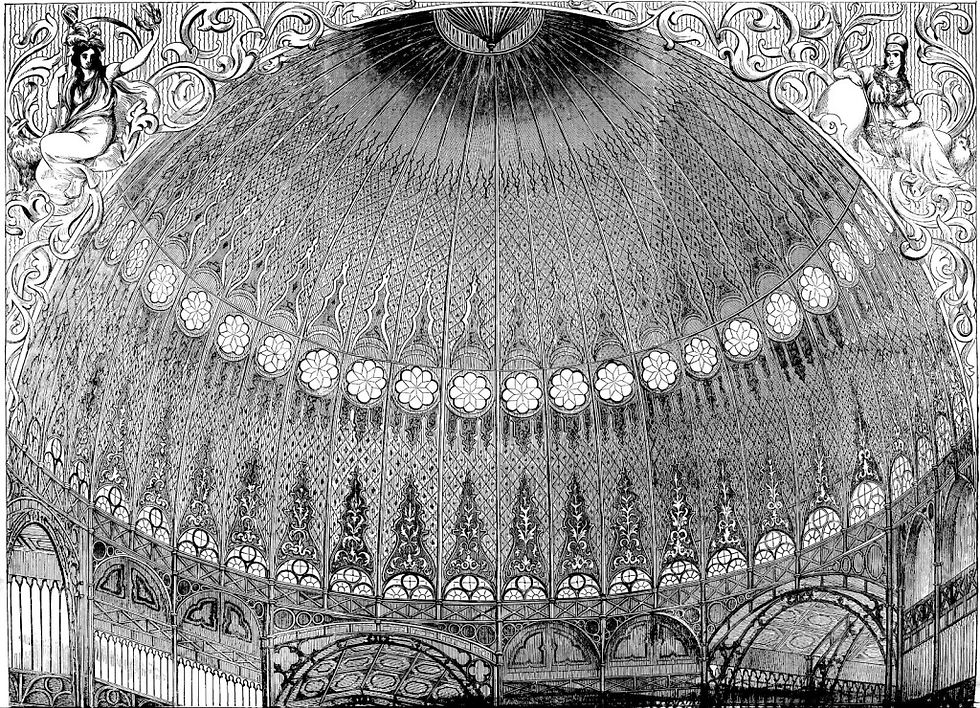

Interior of the New York Crystal Palace, 1853

The remains of the Product Exhibition Hall (now the Peace Memorial) in Hiroshima in the immediate aftermath of the US-led atomic attack in August 1945.

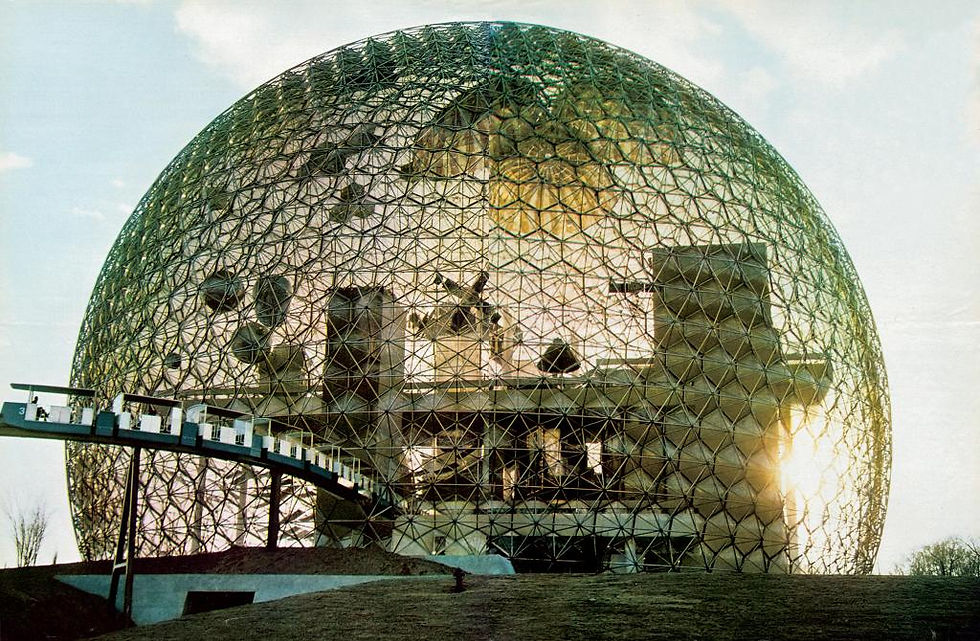

Buckminster Fuller’s geodesic dome created for the 1967 Expo in Montreal.

Unsurprisingly, since then there’s been a strong desire to revisit the dome as a protective structure. Buckminster Fuller’s invested his innovative geodesic structures with an ecological meaning as well as a universal application, taken up by many countercultural communities such as Drop City in the US as a basic, easy-to-assemble architectural kit-of-parts. In the late-1960s, inflatable domes created by the Utopie group, Haus-Rucker-Co., and Archigram suggested the inauguration of a new womb-like architecture that could be truly nomadic, while the bio-domes in the 1972 film Silent Running inverted the optimism of the 1960s. In its bleak vision of an ecologically devastated earth, the only surviving vegetation floats in space in giant geodesic domes. The film concludes with all bar one of the domes being blown up by nuclear weapons – the lone survivor drifting in a post-human solar system.

Geodesic structures in Drop City, a community formed in southern Colorado in 1965 but abandoned by the early 1970s.

Archigram’s Cushicle project, 1966, an inflatable portable structure designed by Michael Webb

One of the giant space-travelling bio-domes in Silent Running (1973)

More recently, the Millennium Dome in London attempted, unsuccessfully, to recover an earlier spirit of optimism, while the Eden Project (2000-2003) in Cornwall created a terra firma version of the bio-domes in Silent Running. Even as the Project transformed a defunct industrial site into en ecological paradise and has become a centre for the promotion of sustainable ways of living, it cannot help but suggest a bleak future for what lies outside its series of gigantic protective domes. And what of the TV series Under the Dome, aired from 2013 to 2015, and which is premised on the mysterious appearance of a massive, transparent and indestructible dome over a small town in America, cutting the community off from the rest of the world? Here, the dome is not a protector; rather, as in the earlier film The Truman Show (1998), the reverse: namely, a structure that imprisons.

The Eden Project near St Austell, Cornwall, opened in 2003.

Still from the TV series Under the Dome (2013-2015).

Perhaps this recent image of the dome as threat reflects a fundamental shift in how we think about the world beyond the human. With the knowledge of what Timothy Morton terms ‘Hyperobjects’ – examples include global warming, nuclear bombs, planets, galaxies, even other universes – the image of the world, or the world beyond, as a dome no longer holds true. In fact, the very opposite – instead of lying beyond us, these hyperobjects envelop us at every turn. For no-one and no thing can be protected from the weather that is a symptom of global warming, from the energy emitted by radioactive particles, or from the gravity waves that we can barely comprehend, let alone feel. In our fearful times, bunkers seem safer than domes; and, as in the 2011 film Take Shelter, it is the bunker that holds out such a hope of protection, perhaps reverting back to the meaning of the earliest burial domes themselves.

#CrystalPalace #DropCity #1967Expo #ManhattanDome #London #burialsites #MillenniumDome #TimothyMorton #castiron #HausRuckerCo #Atomicweapons #Utopie #TheTrumanShow #mounds #Montreal #hyperobjects #BuckminsterFuller #bunkers #NewYork #geodesicdome #EdenProject #TakeShelter #disaster #SilentRunning #HaghiaSophia #StAustell #Istanbul #biodome #megalithic #Cornwall #HiroshimaPeaceMemorial #GastonBachelard #glass #inflatables #domes #Archigram #CenotaphforIsaacNewton #EtienneLouisBoulle #UndertheDome

Comments