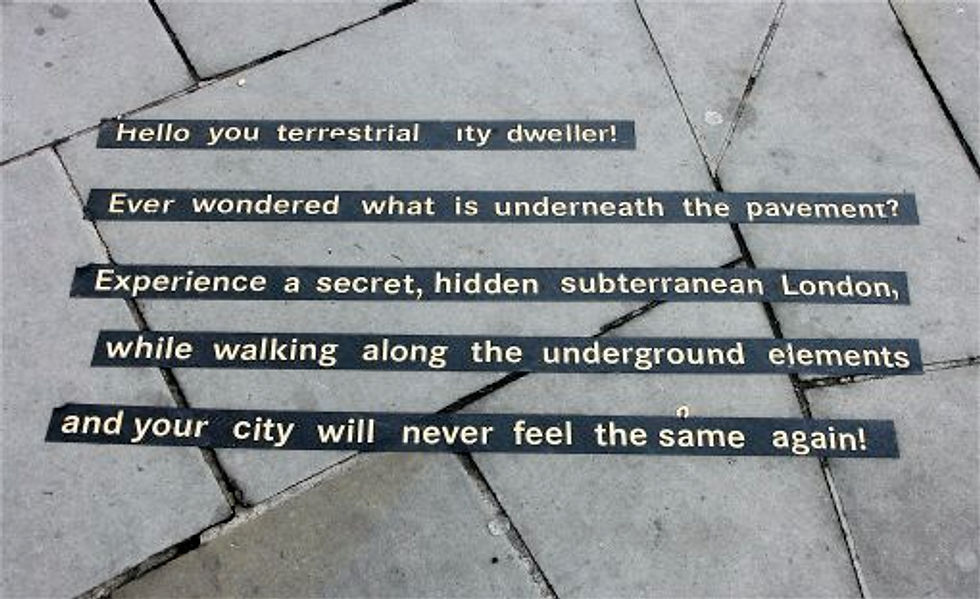

Greeting at Ludgate Circus

Last autumn in London, city slickers passing Ludgate Circus would have been forgiven for not responding to this salutation on the pavement. Barely noticeable and oddly phrased, this was a piece of graffiti that looked more like an official instruction from an unknown but benign authority. London is overcrowded with subterranean spaces, but on this particular day, I could not help but feel that pedestrians were being directed to the disused Kingsway tram tunnel, temporarily reopened at that time for tours of a work of installation art titled Chord. Conceived by the British artist Conrad Shawcross, Chord consisted of two giant, mechanical machines that wove a thick spiral of rope from innumerable spools of coloured string. Following the old tram tracks underground, these two machines moved very slowly away from each other in the Kingsway tunnel, connected by their woven rope until it was cut and the process begun again.

Chord, Kingsway tram tunnel, October 2009

Chord is one of a number of recent art projects that make use of disused underground spaces – in both London and other British cities. Yet, perhaps unsurprisingly, the underground spaces themselves have tended to be the bigger draw than the art which they house. The Kingsway tram tunnel is one of many of London’s ‘lost’ subterranean spaces. It opened in 1902 and was part of the redevelopment of Holborn that cleared away slum housing, replacing it with a broad, tree-lined avenue. Underground, the tram tunnel provided a north-south route that connected London’s tram lines and eased traffic congestion. Closed in 1952, its main use since has been for storage and for film and television sets.

Abandoned cars in the Kingsway tram tunnel

In fact, it is difficult to separate reality from fiction in the Kingsway tunnel. Is the 1970s Ford Cortina of its time or the remnant of a film set? Why are there old Tube maps on the walls? Much of what is there, including the boards full of fake-posters seen below, are the detritus of a more recent venture when this space was used as a fictional Underground station ‘Union Street’ in the 2008 film The Escapist. But how can we explain the combination of Victorian and post-War print here? Are some of these real, others part of the film? Or are they part of several different films, each new one pasting over its forebear? Or are they even, perhaps, a realistic evocation of a tube station billboard when an old poster is removed, exposing the multiple layers of the past beneath?

Posters in the Kingsway tram tunnel

This mixing up of the real and fictional makes this a natural space for art installations: after all, they are only continuing an already established tradition. Of course, many other London locations have been used in cinema, but those underground maintain the traces of that interaction in a much more tangible, strangely uncanny, way.

Commentaires